Hell Dogs is written by Akio Fukamachi with art by Keita Iizuka. Please support the official release!

This may be a book review blog, but we’re starting out strong with a review of something that is not a book. Now please don’t get upset with me: I know that Goodreads acknowledges comics (oh, excuse me, Graphic Novels) and manga, but I’m just gonna put my cards down right here and say that I don’t think reading a comic is the same as reading a novel, and I’ll tell you why.1

Aristotle has this concept called phantasia– kidding. I’m kidding, don’t worry.

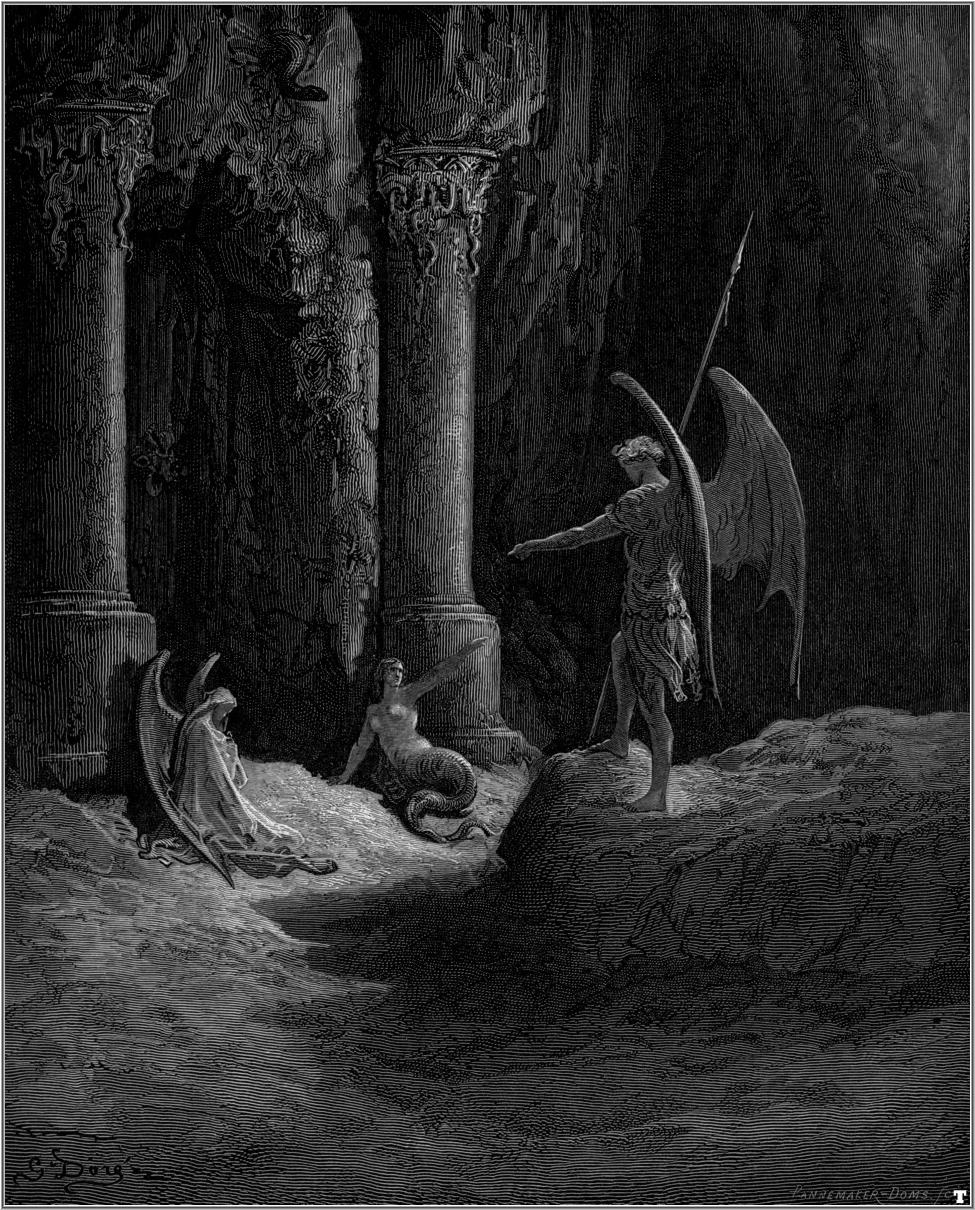

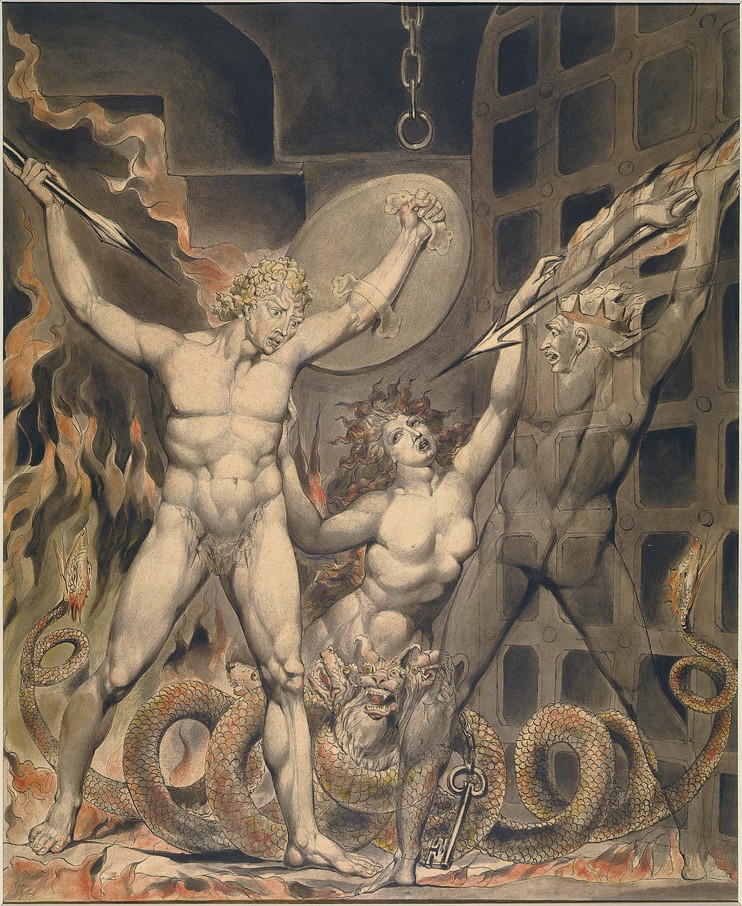

Put simply, I think that reading words and looking at a picture are two different exercises that scratch different parts of the imagination. Words and pictures can each evoke things that would be impossible (or at least, very difficult) for the other. With words the writer is trying to stimulate the reader’s imagination to create images (that would be the phantasia), while with pictures the artist has already made the image and now wants the viewer to react to it and appreciate it, picking it apart as if it were words, but on a more instinctual level. There are still levels of comprehension and imagination at work in both cases, but they’re being used in different ways and with words there will always be an element of ‘work’ which is not present with pictures, in that the reader is the one who has to put the image together. Of course, an illustration in a book might be used to ‘illustrate’ the image that the author is trying to convey, but even these can vary greatly depending on the artist.

I don’t want to harp on this too long but my opinion is essentially that in a comic book (a good comic, mind you. Bad comics and bad books are frequently both bad in the sense that they fail to stimulate the imagination properly) will rely less on the words and will, at climactic moments, allow the imagery to take over. Novels do something similar with passages of description, but in a visual medium like a comic the effect is heightened due to things like page layouts, colours, structures, all that. The horror author/artist Junji Ito places his ‘reveals’ in such a way that they ‘jump’ at the reader when they turn the page, and it would be very hard/kind of silly to do something like that with a novel.

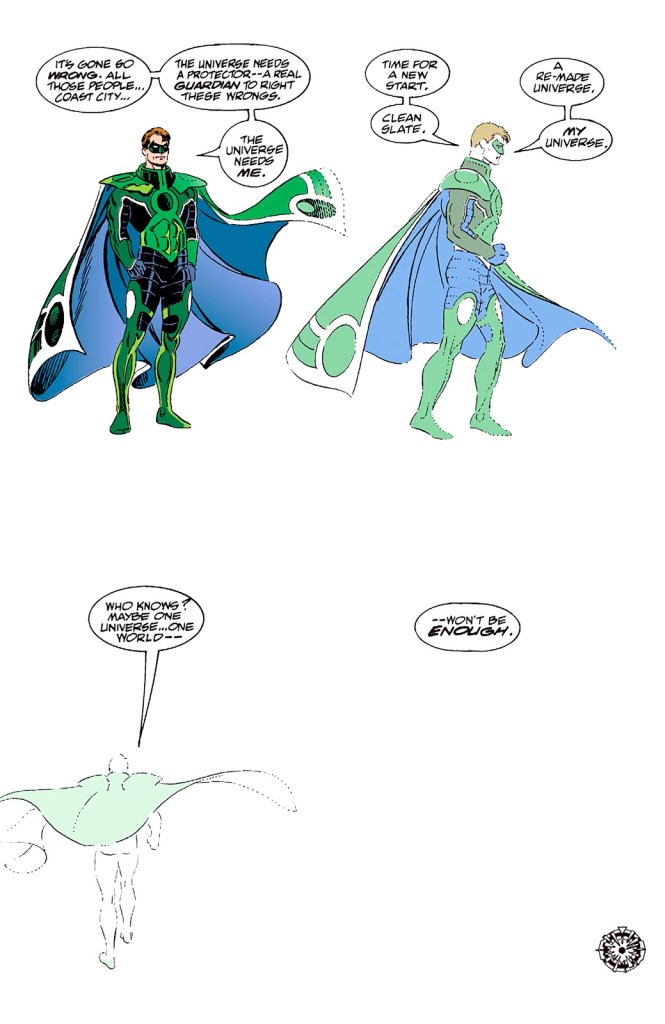

As an example, take a look at this page from Zero Hour (DC, 1994). Parallax (the green guy) is about to re-make the universe according to his own designs as part of his deserpate attempt to reclaim the life that was ripped from him. You could achieve something similar in prose, but look at how beautifully simple the effect here is.2 The pure white light contrasted with the sinister tone of his speech highlights Parallax’ deluded mental state but also his isolation. He walks away from us, mirroring his own departure form humanity and from recognisable superheroic morals. This simplicity matches the events and the tone- it’s as if Parallax’ power to unmake goes beyond his own reality and has begun to bleed through into ours, dissolving the structure of the comic in which he exists. This is one of my absolute favourite design choices in basically any medium.3

I think it’s important to stress that the medium of a comic book isn’t ‘worse’ than a novel, it’s just different. And that leads us to my next point.

In my opinion the real meat of the ‘is reading a comic the same as reading a book’ question isn’t so much about the mechanics as it is about the morality of a comic vs a novel. There’s a desire, I think, for validation and legitimacy of one’s entertainment habits. And it’s not even because I think comics are bad – there are plenty of really terrible novels which are certainly less interesting and more silly than the average comic book. Some comic books are beautiful and thought provoking and deal with real, serious issues in a very sensitive fashion, and they deserve to be interpreted and examined in just the same way as a novel.4 That’s the beauty of the medium and so I think casting comics as some kind of vaguely apologetic subclass of novels does an injustice to everyone involved.5

Now, if the ‘is reading a comic the same as reading a book’ conversation was bad, then the ‘is reading a manga the same as reading a book’ conversation is even worse. My attitude to this is the same as my attitude to comics: most manga is really bad, but then so are most novels, so I don’t think the argument from morality really holds up since we’re talking about a ratio of 10:1 dogpiss, and that’s being generous.6

All that to say that Hell Dogs is an absolute treasure and it’s a real, genuine shame that it isn’t more well known. In fact, as far as I know there is no official English translation, so the only way to read the story if you don’t know Japanese is through fan scanlations.7 This manga is (I believe) an adaptation of a novel. There’s also a film which you can watch on Netflix, but the manga and film are quite different plot-wise so if you like one you may not find what you are looking for in the other. The novel isn’t (yet!) translated into English (but it is in French), so my primary point of reference here is the manga.

The story revolves around Idetsuki Gorou/Kanetaka Shougo, a police officer who goes undercover in the Yakuza in order to take down Toake, the leader of the Tousho Group. It is soon revealed that Toake himself was also an undercover officer and what’s more a friend of Idetsuki/Kanetaka’s boss, Anai, who is coordinating the whole operation from behind the scenes. What follows is a seriously suspenseful thriller in which Idetsuki/Kanetaka struggles with his own identity and the rival forces who demand his loyalty, driven all the while by his desire for revenge against the gangsters who murdered his friend.

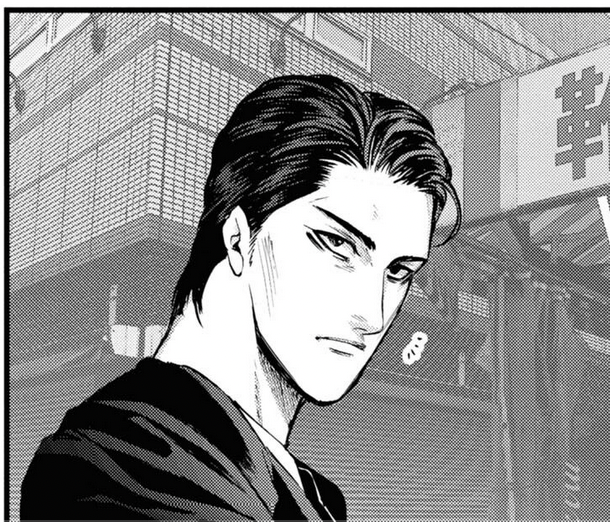

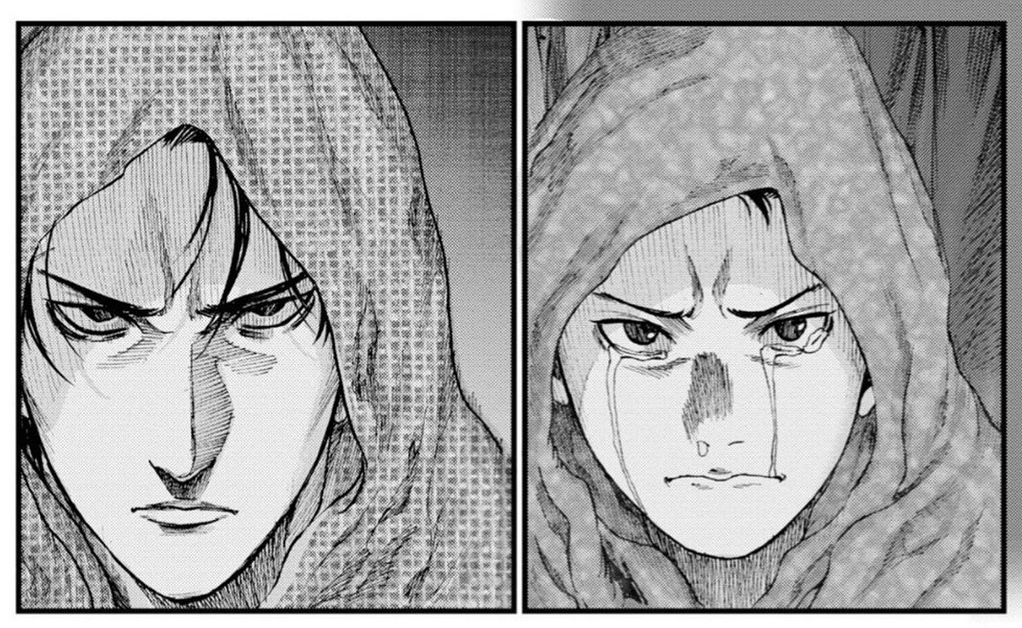

The artwork is very stylish and neat and reminds me of a more modern take on the work of Ryouichi Ikegami, who is well known for illustrating numerous Yakuza stories throughout the 80s and 90s, most notably Sanctuary and Crying Freeman, although he is still working to this day (I particularly liked Adam and Eve written by Hideo Yamamoto). Kanetaka has a very pretty and expressive face in the vein of Ikegami’s bad-boy gangsters, accessorised with a few rakish scars as the story goes on. 8

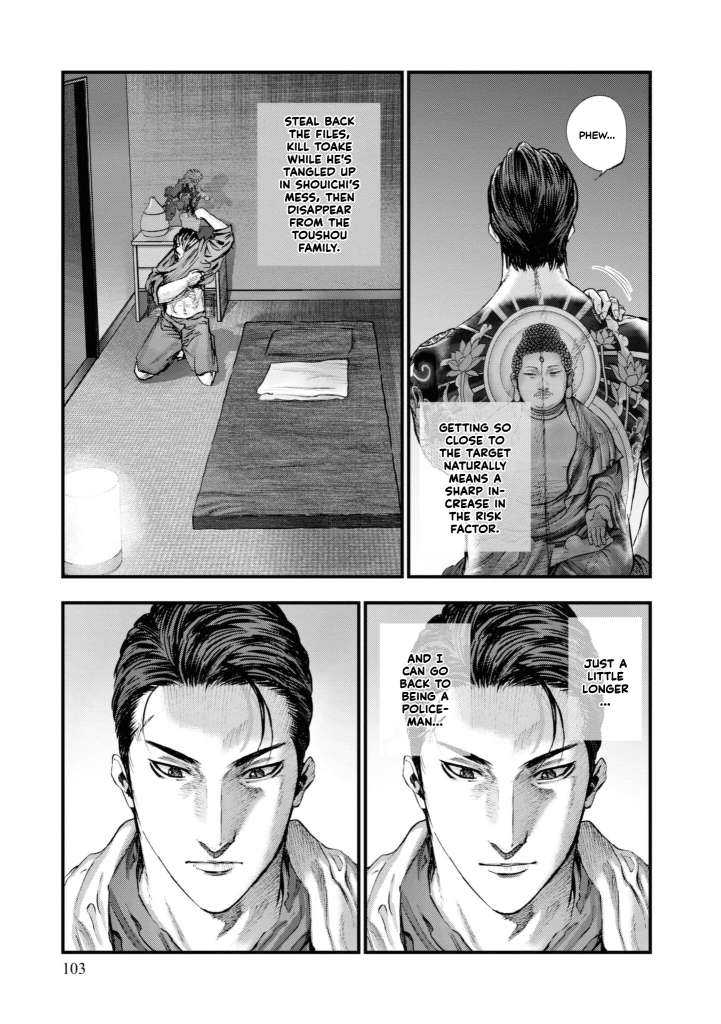

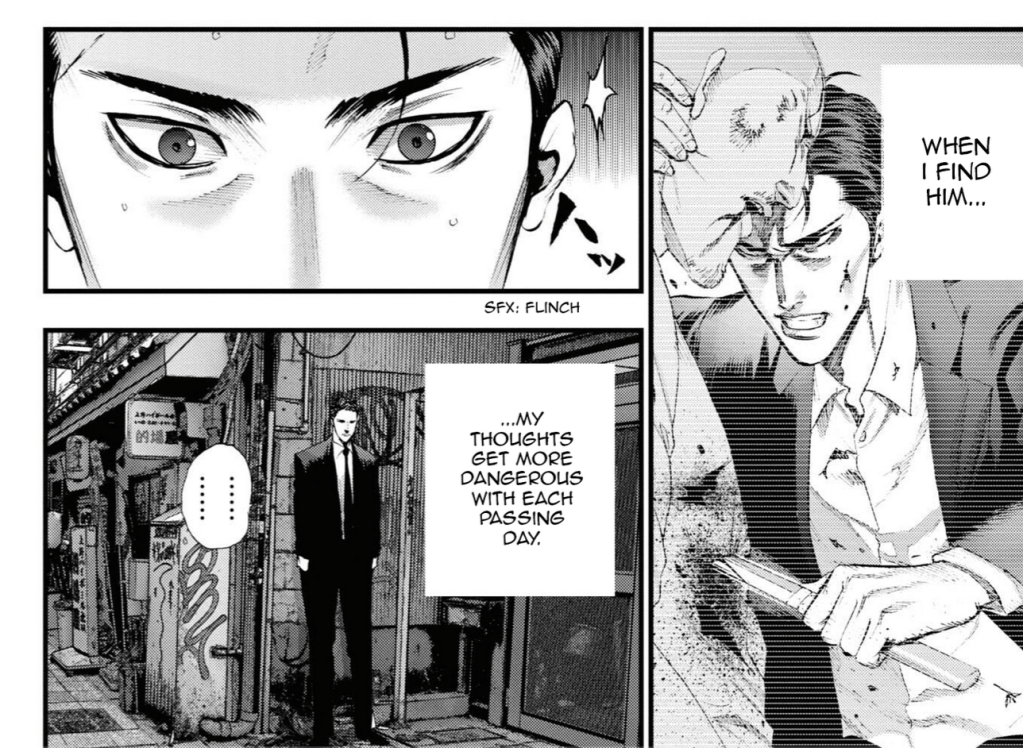

This isn’t a cheerful story, not even from the start. The few moments of happiness that Kanetaka experiences are punctuated by immediate sadness as he wonders what kind of person he has become to laugh at gangsters’ jokes or share a meal with murderers. His refrain of ‘when I go back to being a cop’ has a strain of melancholy as if he knows that it’s hopeless but doesn’t really want to admit it. The artwork hints at what Kanetaka is afraid to say, demonstrating that quality which we discussed in the opening of this review. 9 We, the viewer-reader are privileged to see things that Kanetaka cannot – and I don’t mean alternate character viewpoints (we stay with Kanetaka throughout). We see the changes in expression, the hardening of his face, and the ease with which he adapts to violence. Again, not something that you could convey in writing, especially not in the 1st person. The manga (in translation, but I presume in the original, as well) adopts a mix of 1st person and 3rd person narration, for Kanetaka’s thoughts and an omniscient narration respectively. This is pretty typical for manga and comics, but again it’s not something that you could do in a novel unless you were very smart with it. The medium allows for an intimacy beyond what you could accomplish with so many words.

A central theme of this story is hope, or perhaps false hope. To immerse himself in the Yakuza Kanetaka has had his face and body altered with surgery and tattooing, and his previous (adult) face is never shown, letting us know that what was in the past is now lost. The dialogue discloses this in drips and drabs, letting the artwork reveal what Kanetaka is too ashamed or deluded to reveal himself. For all his talk of going back to the police, Kanetaka sure adapts to being a gangster well and proves his determination to take down Toake and complete the mission multiple times by performing acts of astounding violence. The irony is that in his desperation to go back to his old life, he is in fact slipping further away from it like someone swimming desperately against a current as it pulls him out to sea. It’s a common saying that a dog caught in a trap will chew off its own leg to escape, and the violence in Hell Dogs is weighted with this desperation. The violence and cruelty of his behaviour makes for a disturbing contrast with his almost childlike trust in the police and his belief that he can still go back to being a ‘good person’ once all this is said and done.10

The author doesn’t shy away from showing the violence and cruelty that the yakuza employ, and which Kanetaka frequently participates in – in fact we find out early on that he has become famous among gangsters due to his talent for butchery. If you aren’t a big fan of ultra-violence then you probably won’t like this manga. A particularly brutal scene sees Kanetaka beat a woman into unconciousness, and in the following chapter he watches as she is stripped naked, tortured, and then internally examined to look for hidden trackers. However, the story also avoids exploitation and it doens’t feel gratuitous – the violence is never performed for the sake of it and there is no room for ambiguity when it comes to the negative presentation of Kanetaka’s growing enthusiasm for torture and murder. The inhumanity of the violence contrasts with the strongly articulated connections between friends and colleagues. We come to see the Yakuza as Kanetaka does; as real people with friendships and loves and worries who are also capable of obscene criminal deeds. The issue of Kanetaka’s loyalty comes to the fore in the final chapters and it is genuinely difficult to predict what he will do when his back is against the wall.

There are really two stories going on here: the conflict between rival Yakuza groups, which is told through dialogue and infoboxes, and then the internal conflict between the Kanetaka and Idetsuki personas that the protagonist adopts, which is told mostly through visuals and through inner narration. The latter is the more compelling of the two major narrative lines, and the moments when we are in Kanetaka’s head are the most exciting and often heart-wrenching. Kanetaka engages with the politics of the Yakuza and the Police through the lens of his own inner turmoil and the gangsters’ struggle for control is of little interest to him beyond his immediate concern for his cover.

My first thought of comparison for this manga was the classic Yakuza film series Battle Without Honour and Humanity, which centers on the life and career of Shozo Hirono as he ascends the ranks of the yakuza in post-war Hiroshima. Both Battles and Hell Dogs have as their protagonist a mid-level gangster with a strong if warped sense of justice and an aversion to the underhanded tactics of his peers, who is nonetheless forced to comply even when there is no benefit to himself. His continued engagement with this world that he apparently despises hints at a private shame – a thrill for violence. As the manga went on, however, this comparison felt less apt. Hirono is proud where Kanetaka is pathetic, a beaten dog who crawls back to the kennel and licks the hand that struck him. Perhaps a comparison with Ichi (the eponymous killer) would be better?11

Kanetaka’s inability to make his own decisions speaks to a certain weakness of spirit, and that is really the tragedy of the story. It shows that when you’re so dead set on something – revenge, whatever- it makes you very open to manipulation. The desire for revenge especially will hollow you out, and what will be left when you’re done? This is a common question in revenge dramas, but Hell Dogs tackles it in such a way that it doesn’t feel cliched or predictable. I read this manga as it was being translated at the end of last year and the wait for the last few chapters was agonising because I really couldn’t figure out what Kanetaka would do next.12

Hell Dogs is a tragedy, and a very effective one at that. Having sacrificed his body, family, friends, and morals for the sake of his revenge our hero is left with almost nothing for himself. It’s a notable feature of revenge tragedies that the hero usually expects to die at the end, but Kanetaka is motivated throughout the story by this thought that he will be able to return to what he was before. The entire undercover mission is really a preliminary to his own grand revenge narrative, and so unlike other vengeful anti-heroes Kanetaka does not expect to die, nor wants it. However, as the story goes on and Kanetaka’s memories of the past become more wistful we begin to wonder if the inevitable death has not, on some level, already occured.

I would love to tell you to go and buy the official English release, but since there is no official English translation, then that isn’t an option. This is the sad fate of a number of really excellent lesser-known manga, and with the crackdowns on piracy and scanlations in recent years it is getting harder to share these works. My best suggestion would be to read the manga and recommend it to anyone and everyone who you think would like it and then, if you can, please buy the Japanese physical release. Even if you can’t read Japanese. Donate it, sell it on ebay, keep it – but please do try to support the author.

- I feel comfortable wading into this argument because I was, throughout my teen years, a dedicated comic book fan despite getting endlessly bullied about it by people at school and nagged about reading ‘real books’ by my mother (who I love and who only has my best interests at heart). Trust me when I say that I consistently and passionately argued with my parents over dinner that reading endless second hand issues of Joe Quesada’s 1997 X-Factor run was just as good as reading normal books. ↩︎

- I’m sure we’ve all heard that old line ‘show not tell’, which is one of those common pieces of advice given to amateur writers that, like many such pieces of advice, is actually quite restrictive once you get beyond the level of a total beginner. ↩︎

- The ability to ‘undo’ reality is just endlessly fascinating to me and I love it pretty much every time I encounter it in media, although I think it really works best in a visual format (film, animation, comics). ↩︎

- And some comics are Ulimates 3, which I unfortunately read in high school. Funny story about Ultimates 3- there’s a scan of it floating about online where someone rewrote all of the dialogue as a joke and not only does it not notably change the story, but it’s actually quite hard to tell which version is real and which is the spoof. ↩︎

- This is a peeve that I have in general with media adaptations, actually. Soemething which worked well as e.g. a novel or video game might not work well as a film, but there seems to be this idea that everything good must also be translated into another medium, with the ultimate medium to which all things aspire being a ‘live action’ (therefore more real) film. Some adaptations are great, obviously, but plenty of them are just a waste of time. ↩︎

- And that’s not even getting started on the fact that the vast majority of early fanscans were produced primarily by teenagers and college students in the 90s and 00s, which explains a lot about why those scans are the way that they are. See the infamous Berserk panel below. ↩︎

- Fanscans can be kind of a mixed bag (see the Zetman panel inset above) but in this case the available English fan scanlation for Hell Dogs, which I won’t link but which is very easily found if you know where to look for these things (perhaps on an index… a manga index, if you will), is very high quality and absent the usual ‘quirks’ of fan scanlation. ↩︎

- There is a very interesting interview between Ikegami and Naoki Urasawa, best known for Monster and 21st Century Boys. Ikegami says pretty much right away that it’s no fun to draw a scene without a good looking man in it, which I think is a fine philosophy. ↩︎

- The scanner included some sketches from the artist (name?) and by the looks of things the manga is drawn traditionally and then digitally toned, with the tattoos being added in the digital stage. What the art really did remind me of was Yusuke Murata’s work on One Punch Man, mostly in the ‘clean’ quality of the lines and shading and the intricately sprawling cityscapes. ↩︎

- Kind of reminds me of that epilogue from the Killing Joke about the guy who wants to kill Batman. “[And i’ll] go to heaven when I die”. ↩︎

- Fun fact- the english fanscan of Ichi the Killer was produced by scan-group ‘Band of the Hawk’, who were also responsible for the most widely read (and perhaps the first, i’m not sure) English-language Berserk scan, from whence the wonderful panel below. ↩︎

- I don’t quite know what happened but the translator went AWOL for like 3 months before uploading the last chapter and the wait was genuinely so painful that I ended up reading it through google translate. ↩︎